Faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a technique whereby infusion of faeces (the entire gut microbiota) from a healthy donor is delivered into the gastrointestinal tract of a patient to cure a specific disease by re-establishing a stable gut microbial community. As this procedure is not an actual transplant, the term “faecal microbial transfer” is often used.

In general, moderate effects can be achieved by probiotic and prebiotic products, which increase the number of beneficial bacteria directly (probiotics) or indirectly by providing a substrate for residing beneficial bacteria (prebiotics). For more severe disturbances, however, these measures are not sufficient. FMT provides a more powerful means of modifying the microbiota by replacing or reinforcing it (1).

Although FMT has been utilized for over 50 years, it has recently gained momentum given its high efficacy in eradicating Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Most clinical experience with FMT has been derived from treating recurrent or refractory CDI, the leading cause of antibiotic and healthcare-associated diarrhoea (2).

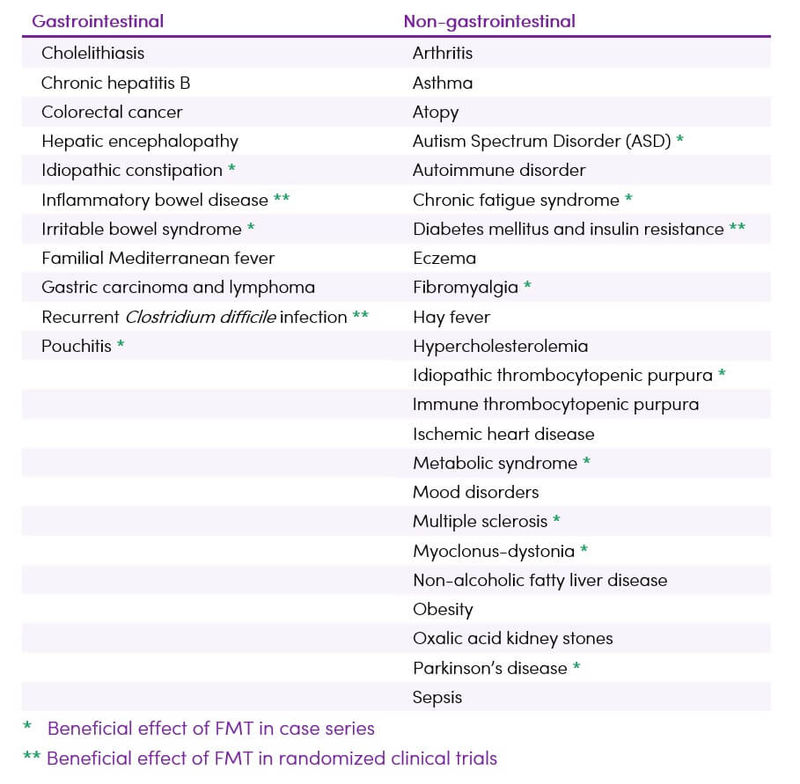

Despite increasing interest in FMT, its full therapeutic potential has yet to be determined. Interest in FMT now expands well beyond the treatment of CDI to other processes with known associations to the microbiota (Table 1).

A consensus report was recently published setting out guidance for the use of FMT in recurrent CDI, IBD, IBS and the metabolic syndrome (1). Currently, it is recommended that FMT in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and metabolic syndrome should only be performed in research settings (1).

FMT poses regulatory challenges to the healthcare industry, in terms of quality, efficacy, donor screening/anonymity and providing quality information to empower the patient to make a choice. The classification of the treatment has yet to be decided in order to determine which regulations apply - is it a gene, cell or tissue transplant procedure? Country-specific legal regulations need to be considered when working with FMT (1). Currently, regulatory authorities in several European countries and the USA treat human faeces as a drug. Exact regulations vary, but the general classification is criticised by several experts as creating a disincentive for research, restricting access to care, and failing to evaluate the long-term risks associated with the process. Instead, classifying stool as a body tissue would be preferable to address these issues (1).

Table 1. Established and potential future indications for FMT (3,4,5)

The FMT process usually involves first selecting a donor without a family history of autoimmune, metabolic, and malignant diseases and screening for any potential pathogens. The faeces are then prepared by mixing with water or normal saline, followed by a filtration step to remove any particulate matter (6). The mixture can be administered via various routes (1,6):

- Administration into the proximal gastrointestinal tract via nasogastric, nasoduodenal tube, nasojejunal tube or by endoscopic procedure

- Administration into the proximal colon by endoscopic procedure

- Rectal or distal colonic administration via enema or colonoscopy

- Combined approaches as well as the oral application of encapsulated preparations

Gel capsules of faecal microbiota is a promising new technique which excludes the need for any gastrointestinal procedure (7,8) and is preferred by patients (9). Private companies already deliver FMT through oral capsules, mainly for the treatment of CDI. However, it is unclear whether these capsules are as effective as FMT itself (10). An alternative for FMT in the future could be the so-called synthetic stool that consists of a mixture of selected beneficial microbial strains (1).

The selection of a donor for FMT is not standardized, although there is general consensus for the need to do so. Initially, donors were typically family members identified by the patient. However, recent studies highlight the practical advantages of using standardized volunteer donors and creating screened biobanks (10).

Figure 1. Faecal microbiota transplantation procedures (3) CC BY-NC 3.0

(A) Donor stool and normal saline ground in a blender (B) Faecal suspension in 50-mL syringes (C) Infusion using colonoscopy

Traditional Understanding

FMT is not new. In the fourth century A.D., Chinese patients suffering from severe diarrhoea were given oral faecal suspensions. Likewise, in the sixteenth-century stool was used to treat diarrhoea, fever, vomiting and constipation. In modern times (1958), faecal enemas have been used as a cure for human pseudo-membranous colitis (11).

Latest Research

Clostridium difficile infections

- FMT is used for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) with efficacy rates of 90%, giving reason for hope that it might also be successful in other diseases where disturbances of the intestinal microbiota are involved (1)

- FMT has been found to be effective and safe in treating CDI in children and young adults with a 86% success rate (12)

- FMT leads to fast improvement of symptoms and generally resolves CDI within days. An open question is whether such a short period is sufficient for the stable establishment of the transplanted microbial community in the host gut (13)

- A recent trial shows FMT to be more effective than both fidaxomicin and vancomycin in resolving recurrent CDI (14)

- The route of delivery (rectal or oral) does not seem to influence the occurrence of adverse events in FMT treatment of CDI (15)

- Comprehensive new British guidelines on the use of FMT for the treatment of CDI have been issued, indicating acceptance as a mainstream treatment option (16)

Inflammatory bowel disease

Intestinal microbial dysbiosis accompanies intestinal inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (2).

- FMT has been shown to be effective in treating recurrent CDI in patients with IBD, however, caution is required, as the IBD flare rate is relatively high (20-50%) (17-20)

- FMT results in a remission of ulcerative colitis (UC) in about a quarter to one-third of individuals based on recent trials (21,22,23,24). However, some individuals did have exacerbations after FMT treatment. FMT appears to be more effective in individuals with shorter disease duration (< 1 year) and relatively mild mucosal inflammation

- Less evidence is available on FMT and Crohn’s Disease. A series of studies have shown a relatively high remission rate (50%), however, study limitations such as heterogeneity and publication bias limit the clinical value of the evidence (25)

- Available evidence suggests that FMT seems to be safe in IBD patients. However, treatment of patients with a severely compromised colon needs to be considered carefully, as the risk for side effects is higher in those patients, and systematic studies in severe disease are lacking. In addition, case reports have been published that demand caution in IBD patients (1)

- The donor composition is a major factor affecting the efficacy of FMT in IBD and studies emphasize the need to define the profile of the “perfect donor” (2,26)

- With regards to FMT in IBD, questions remain, such as (26)

- What is the optimal protocol/technique?

- Does pooled-donor FMT or single-donor FMT provide better efficacy?

- What is the durability of treatment results?

- Should interval dosing be used to maintain results?

- What is the long term safety of FMT?

Irritable bowel syndrome

The intestinal microbiome is thought to play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The composition of the faecal microbiome in IBS patients differs from that in healthy individuals. However, the exact bacteria species involved in the development of IBS remain to be determined. A common feature of IBS is gut dysbiosis, however consuming prebiotics, probiotics, or synbiotics has a limited effect on IBS symptoms (27,28).

- Some recent trials show the symptomatic benefit of FMT in IBS (27,28,29,30). FMT has been shown to reverse gut dysbiosis, normalise bowel habits and reduce symptoms such as abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating and flatus (27,28,31)

- Other trials have found that FMT can change the gut microbiota in patients with IBS, but has less effect on symptoms and quality of life compared to placebo (32,33)

- In a trial in non-IBS-C patients, a significant improvement in symptoms was seen after FMT. However, at 12 months follow-up, the benefit was not statistically significant compared to placebo (29)

- Data on FMT and IBS are too limited to draw sufficient conclusions at this time. Further rigorous clinical trials are needed, including the effect of FMT on IBS subgroups, before the real impact of FMT in IBS is known (33,34)

- The effects of FMT are probably caused by the interaction of the by-products (especially short-chain fatty acids) of food fermentation by the intestinal microbiome on the local immune cells, enteroendocrine cells, and enteric nervous system (31)

Phsychological and central nervous system disorders

Very recent evidence shows that gut microbial dysbiosis may play an important role in central nervous system (CNS) diseases.

- Several case reports have suggested a beneficial role of FMT in treating constipation and non-GI symptoms in patients with neurological disorders, in particular, autism, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease, possibly by regulating immunological mechanisms via the microbiota-gut-brain axis (35)

- The in vivo effects of FMT also provide evidence of bacterial influence on stress and emotion. Experimental studies show FMT can transfer anxiety-like phenotypes from donor to host, and vice versa (36,37), providing further evidence that the microbiome contributes to the pathophysiology of anxiety and depression (38)

- No studies so far have attempted to establish a comprehensive psychological profile of the effects of FMT in humans. Reports of FMT for the treatment of anxiety and depression in humans have not yet been published, but it is an area currently under investigation. Once the mechanisms of bacteria-brain communication are better understood, FMT may hold some promise in the treatment of anxiety and depression (38)

Metabolic disorders

Many studies have shown that the gut microbiota plays a role in all aspects of the metabolic syndrome, including insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, atherosclerosis, hepatic steatosis, hypertension and obesity. Growing evidence suggests that the success of bariatric surgery is due to its effects on the microbiota (39). FMT may represent an alternative and effective therapy (11).

- Recent experimental and clinical evidence points toward a possible role for gut microbiome manipulation in re-establishing energy homeostasis (40)

- Evidence for FMT in the treatment of obesity is currently preliminary. To date, investigation in FMT for the treatment of adult obesity or type 2 diabetes has been limited to a single small pilot study of middle-aged men with metabolic syndrome. Six weeks after FMT, treated subjects had a 75% increase in insulin sensitivity and favourable changes to gut microbiota that included greater bacterial diversity and a 2.5-fold increase in butyrate

-producing bacteria (41). However, the study was not continued long enough to evaluate the full potential of therapy, notably on body weight and composition

-producing bacteria (41). However, the study was not continued long enough to evaluate the full potential of therapy, notably on body weight and composition - Whilst FMT in humans offers so much promise, it is not yet clear whether it actually leads to significant weight loss. The reverse effect (lean to obese), however, has been demonstrated as the result of the use of an overweight donor for the treatment of recurrent CDI (42). The donor was a young, obese relative undergoing rapid weight gain at the time of donation. The recipient was an individual who had never been obese. After receiving FMT, the recipient had rapid unintentional weight gain and increased appetite that could not be explained by recovery from CDI alone. It is important to note that this observation is a case report, however, it is consistent with in vivo studies where FMT from obese donors to germ-free animals transmits the metabolic phenotype (43). Regardless, the results of this report have affected FMT protocol at many institutions that now exclude obese donors from donating (10)

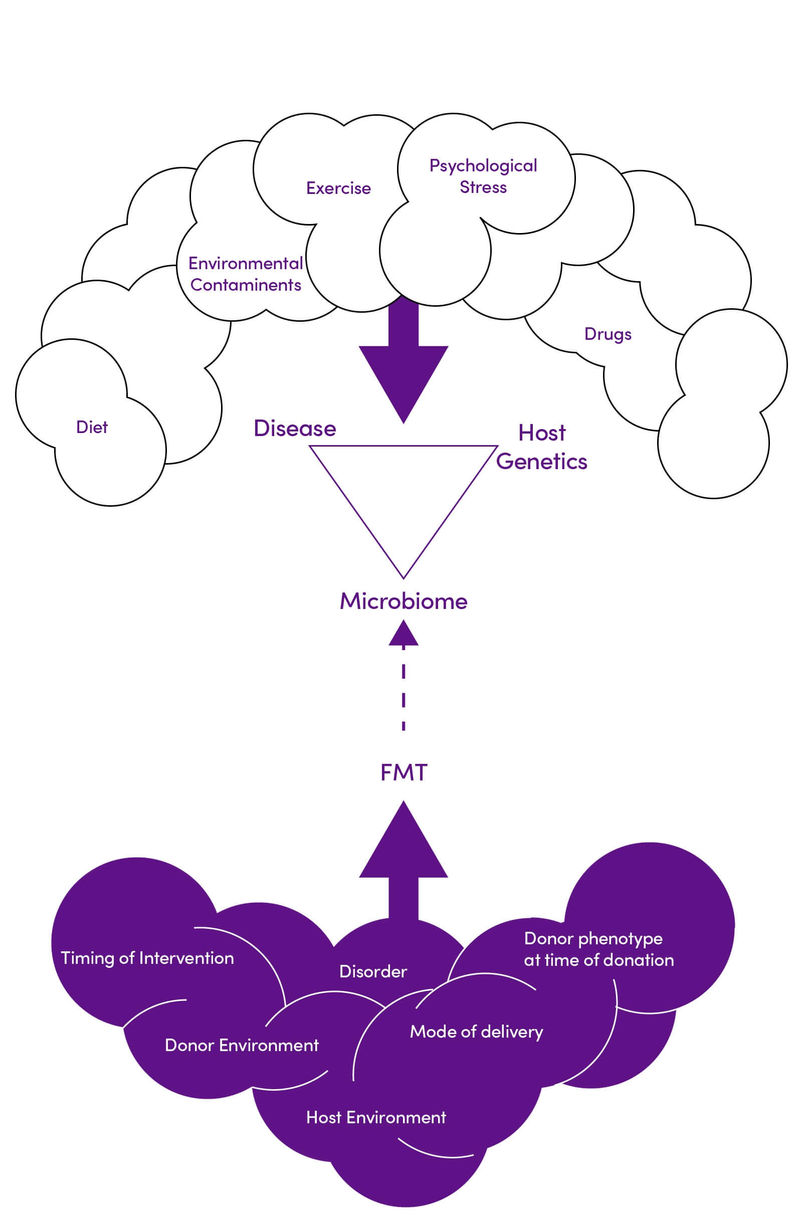

- The duration of the effect, treatment composition, and mode of delivery required to achieve optimum weight loss must be established. In addition, there are many factors affecting an individual’s metabolic syndrome risk and response to FMT that need to be understood in clinical practice (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Environmental and genetic interactions impacting the efficacy of FMT in diabetes and obesity. Adapted with permission from (11) CC BY 4.0

Other conditions

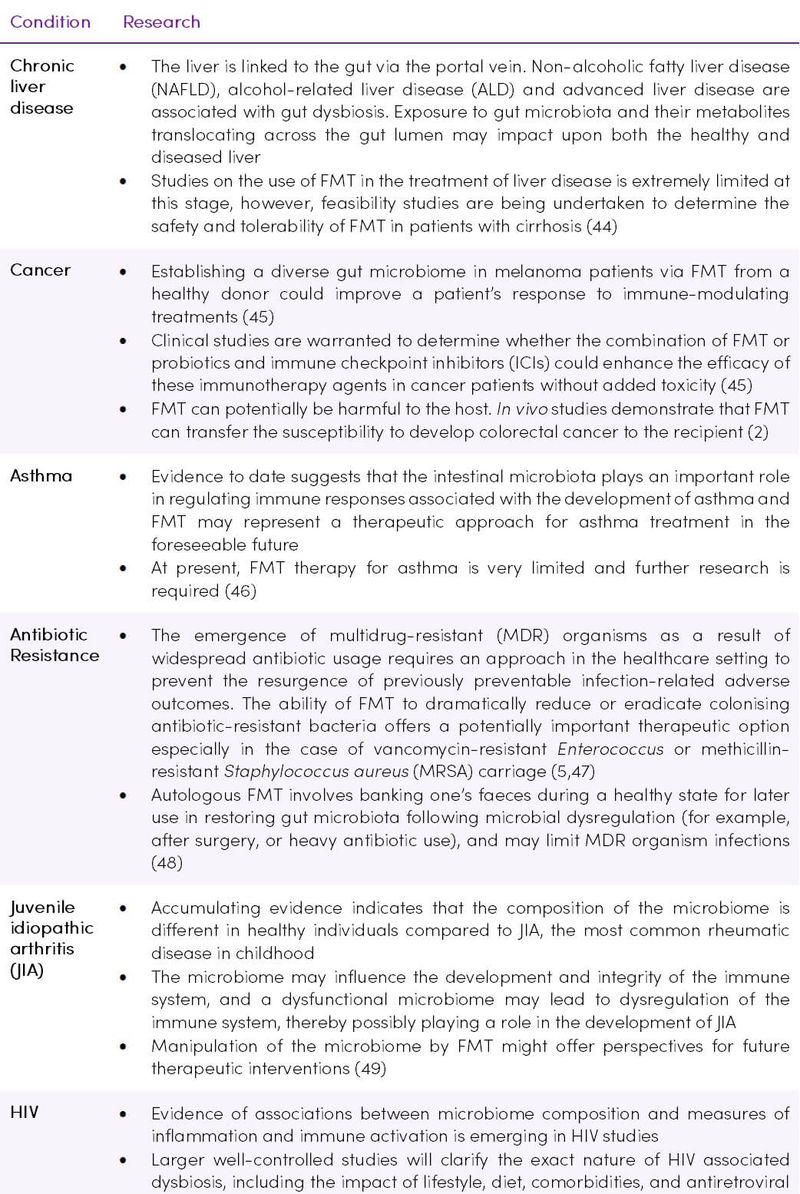

Other conditions which are known to be influenced by the microbiome are being considered as future candidates for FMT therapy (Table 2).

Table 2. Investigation of FMT procedures in various conditions

Cautions and concerns

Adverse events

Although hundreds of individuals have undergone FMT, few negative outcomes have been reported, even in immunocompromised patients (51). The majority of negative symptoms reported are mild and self-limiting, including diarrhoea or fever, however serious adverse events including bacteraemia, perforations and death (due to bacteraemia) have been reported (10,52). Risks can be limited by systematic and careful screening of the donor (1).

Table 3. Short-term or potential long-term adverse events of FMT. Adapted from (3) CC BY-NC 3.0

.jpg)

Challenges

Challenges regarding the research and clinical implementation of FMT include:

- Difficulty in finding accurate measures of adverse reactions. A vast majority of recipients are ill and it is difficult to differentiate between normal disease progression and the effects of FMT (10)

- The spread of transmissible disease, while not reported, is still a viable threat, especially to the immunocompromised (e.g. IBD patient on immunomodulatory therapy, HIV patient with CDI). These reports underscore the importance of rigorous donor screening (10)

- Today we know that FMT may also transfer host phenotype (40). Examples of this include the potential to transfer the obesity phenotype (discussed above), or the transferring of atherosclerosis susceptibility from donor to host via FMT in vivo (53)

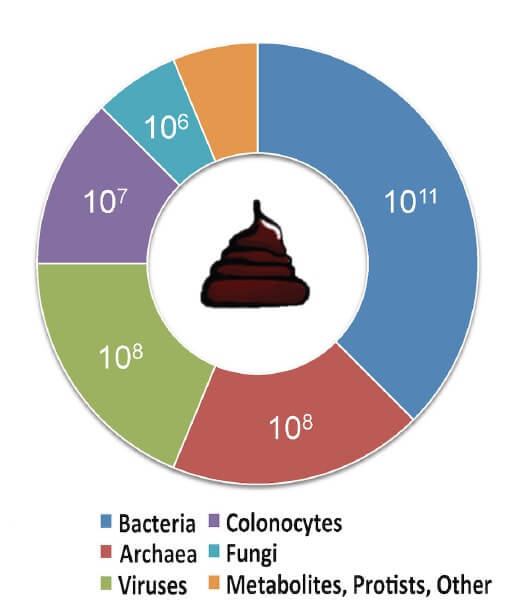

- In addition to viable bacteria, nonbacterial matter such as viruses, fungi and metabolites may also be transferred into the recipient’s intestinal tract. It is essential to determine the potential effect of the transfer of these individual components (Figure 3) (54)

Figure 3. Estimated composition of human faeces. Adapted from (54) CC BY 4.0

- Several aspects need to be explored before applying FMT as a routine clinical procedure, including the suitable donor microbiome and the genetic relationship between the donor and recipient since genetics is one of the important factors influencing the microbiome. It seems that not all healthy donors are suitable and that the donor intestinal microbiome is important for successful FMT (55)

- The effect of FMT decreases over time and hence an important question that still needs to be answered is whether this is due to recolonization with the initial microbiome and, if so, whether this is due to the genetic composition of the individual (31)

- A crucial aspect missing from the current understanding of FMT is the role that host factors, both genetic and immunological, play in treatment efficacy (13)

Takeaway on Faecal Microbiota Transplantation

- FMT is a promising treatment for a variety of diseases in which the intestinal microbiota is disturbed. For indications other than Clostridium difficile infection, more evidence is needed before more concrete recommendations can be made. Currently, it is recommended that FMT in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and metabolic syndrome should only be performed in research settings (1)

- There is limited data in children, but initial reports appear encouraging that FMT is effective for recurrent CDI and seems to be safe, at least in the short term, in children with IBD (56)

- The psychological stresses and social stigma associated with faeces mean that some patients find FMT to be an unappealing treatment. However, a survey of CDI patients found that regardless of FMT’s unappealing nature, patients are willing to try it (9)

- Currently, despite the use of antibiotics and probiotic interventions to modulate the gut microbiota, FMT still represents a more comprehensive approach to restore the gut microbiota ecosystem

- FMT has the advantage over probiotic or symbiotic therapy of repopulating the whole dysbiotic gut milieu, but the optimal route of administration, duration of treatment, and durability of response remain to be determined (44)

- FMT should be administered by strictly regulated healthcare providers (16)