A recent study published in Nutrients indicates that malnutrition and loss of muscle strength can remain long after the acute phase of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection and highlights the need to consider nutritional status in the recovery from COVID-19 (1).

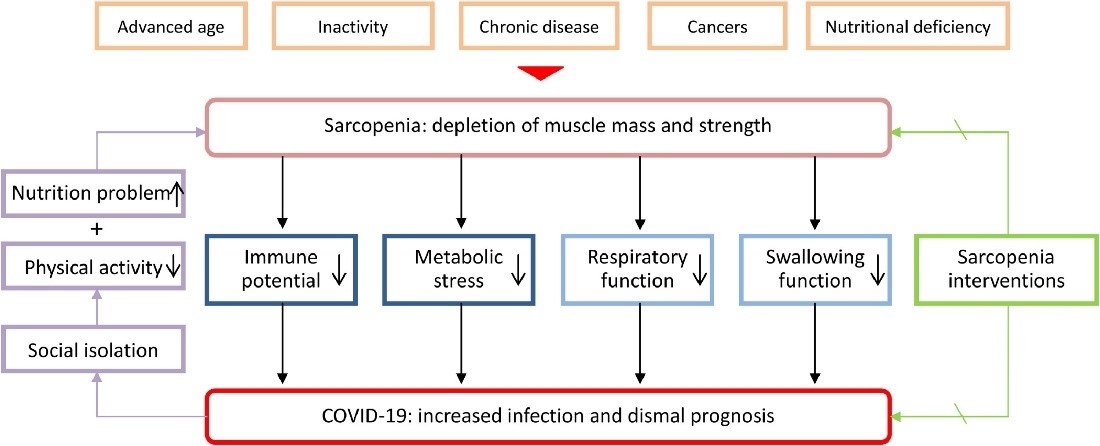

During the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, patients are at risk of losing 5-10% of body weight, and malnutrition is common, particularly among hospitalised COVID-19 patients (prevalence of up to 50%) (2,3,4). Malnutrition results from the dual contribution of symptoms that reduce nutritional intake and absorption and systemic inflammation that drives accelerated muscle loss and hypermetabolism (1,5). In addition to malnutrition, patients may present with acute loss of muscle mass and function (acute sarcopenia), which is aggravated by reduced oral protein intake, immobility and prolonged hospitalisation, presence of chronic disease and advanced age (6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interactions between sarcopenia and COVID-19 (7) CC BY 4.0

Many of the signs and symptoms noted to frequently persist after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, including dyspnoea, fatigue, loss of smell and taste, gastrointestinal issues, and inflammation, can impact and potentially worsen nutritional status (8,9,10). Known as long COVID, these symptoms can persist for more than six months and have been observed in those with asymptomatic, mild, and severe COVID-19 (8). However, the long-term nutritional consequences of COVID-19 are not yet fully understood.

In this prospective cohort study, researchers assessed persistent symptoms, nutritional status, and changes in muscle strength and performance status (PS) 30 days and six months after hospital discharge in COVID-19 survivors (March & April 2020).

Nutritional status was assessed using BMI and weight loss (%) compared to pre-illness weight, with the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria and French recommendations used to diagnose malnutrition. Muscle strength of arms and legs was evaluated using a self-evaluation of strength (SES), with an SES score

At home 30 days post-discharge (n=288), 136 patients (47.2%) presented with a persistent impairment as assessed by malnutrition (33.3%), and/or reduced muscle strength (SES <7) (26.3%) or limitation of daily activity (performance status ≥ 2 ![]() ) (24.3%).

) (24.3%).

These patients received dietary counselling, nutritional supplementation, adapted physical activity guidance or physiotherapy assistance or were admitted to post-care facilities.

At 6 months post-discharge (n=119), 36.0% had persistent malnutrition (15.1% with severe malnutrition), 14.3% had reduced muscle strength (SES <7) and 15% had a performance status ≥ 2 ![]() .

.

The most frequent symptoms at 6 months post-discharge were fatigue (16%), psychiatric disorders (mood disorders, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress syndrome) (10%), dyspnoea (7.6%) and neurological symptoms (neuropathy, headache, impaired memory and concentration or cognitive impairment) (4.2%).

Interestingly, in patients with impairment at 6 months, obesity was significantly more frequent than in those without impairment (52.8% vs. 31.0%), and these patients were admitted significantly more frequently to ICU (50.9% vs. 31.3%). Obesity is a common co-morbidity in COVID-19 patients and has been shown to increase the risk for hospitalisation and poorer outcomes (10,11). The current study’s results highlight that obesity may mask malnutrition and muscle loss, increasing the risk of sarcopenic obesity ![]() .

.

There are some limitations to this study. The degree of muscle mass and functional loss may have been influenced by the patient’s pre-COVID medical and functional condition, especially in older adults. Furthermore, the study relied on subjective measures of muscle strength and did not consider confounders, such as micronutrient deficiency (e.g., vitamin D) which may influence muscle condition (13,14).

Regardless of these limitations, the study highlights that nutritional status needs to be considered in the recovery of COVID-19 patients. Therefore, targeted nutritional therapy is required to improve nutritional status, promote recovery, and reduce the risk of late complications.