Chronic stress can affect physical and psychological wellbeing by causing various problems, including anxiety, insomnia, high blood pressure, inflammation, and a weakened immune system. The consequences of chronic stress are serious and can lead to chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, depression, and obesity (1).

The vagus nerve, a cranial nerve that connects the brain to many body systems, plays a crucial role in the stress response via the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the microbiota-gut-brain axis (2). Therefore, supporting healthy vagus nerve activity can improve resiliency to and recovery from physiological and psychosocial stress, improve emotional regulation and lead to better physical and mental health and wellbeing.

Electrical and transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation methods are now used for treating conditions such as epilepsy and depression (3). However, there are simple and sustainable ways to improve stress resiliency, health and wellbeing by improving vagal tone.

Vagus nerve structure and function

The vagus nerve, the largest and most complex of the twelve cranial nerves, is actually a set of nerves connecting most of the major organs between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract (4).

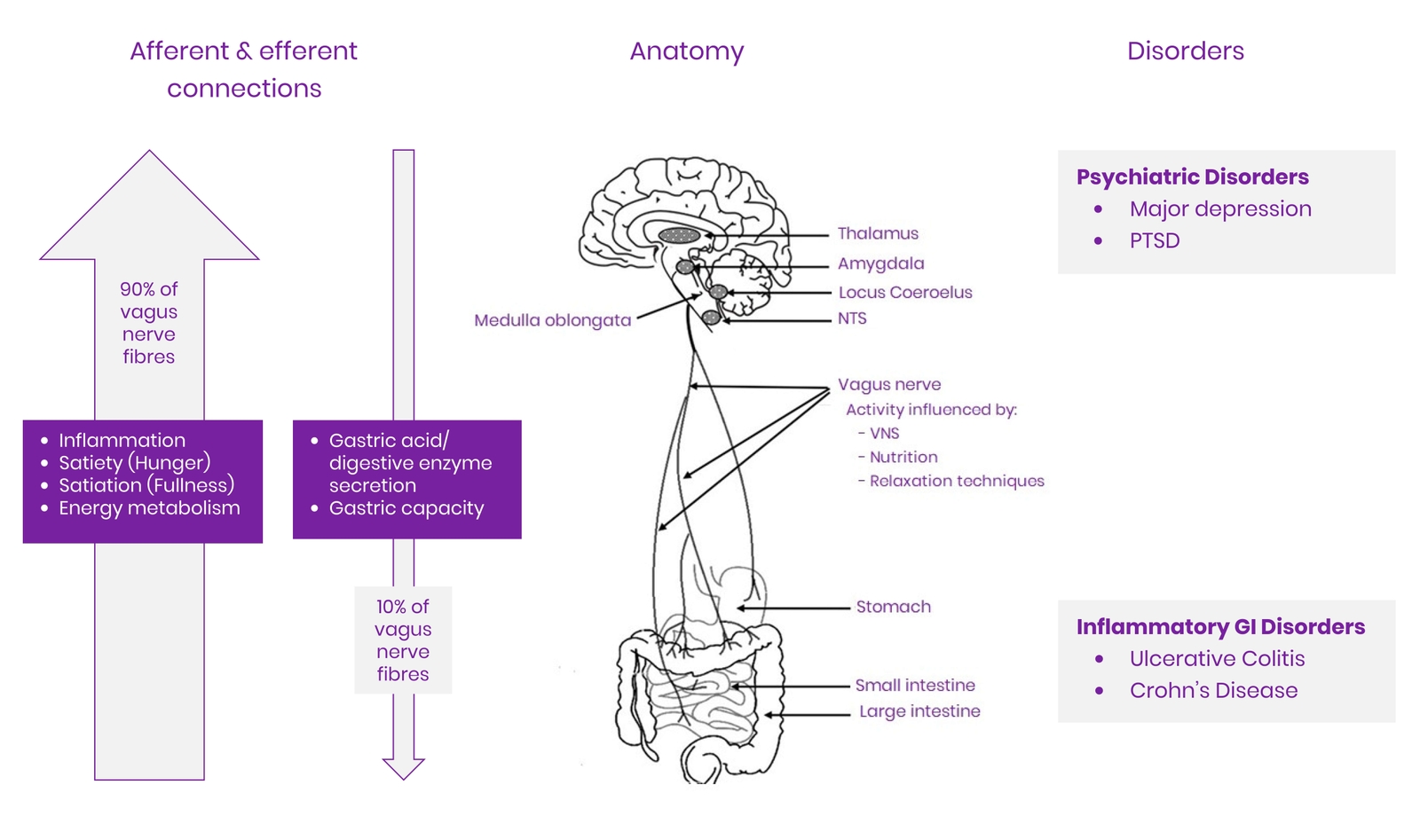

The word vagus is Latin for wanderer (5). As the name implies, the nerve branches numerous times from its origins in the medulla oblongata in the brain and projects to major visceral organs, including the heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract, independent of the spinal column (5).

The vagus nerve relays signals from the brain to the body (efferent) and the visceral organs to the brain (afferent). Physiologically, it plays a critical role in sensory, motor, and parasympathetic functions. These include the inflammatory response, respiration, digestion, heart rate, food intake and satiety, swallowing and speech (2,5).

The vagus nerve is often described as the mind-body connection because it provides a major neural connection between the gut and brain and plays a crucial role in facilitating signalling along the microbiota-gut-brain axis (5,6). The vagus nerve can sense microbial metabolites through its afferent fibres and transfer this gut information to the central nervous system (CNS), where it is integrated into the central autonomic network to generate a physiological or behavioural response (6).

One of the most important roles of the vagus nerve is regulating the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) (rest-and-digest response), which acts as a counterbalance to the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response). To achieve this, efferent vagal neurons release acetylcholine into various organs, which helps facilitate blood pressure regulation, heart rate, respiration, and digestion to promote rest, repair, and growth (2,5). The vagus nerve is therefore essential for promoting a healthy stress response and enhancing physical and mental resilience.

Figure 1 Overview of the anatomy and functions of the vagus nerve and related disorders. Adapted from (5) CC BY

Vagal tone and its effects on physical and emotional health

The activity of the vagus nerve is referred to as vagal tone, and a healthy vagal tone supports the ability of the PNS to counterbalance the SNS. Individuals with a higher vagal tone can regulate bodily functions more readily, including respiration, metabolism, and cardiac activity, than those with low vagal tone (2,5).

The time interval between successive heartbeats, called heart rate variability (HRV), is often used to indicate vagal tone. Higher efferent vagal activity triggers neurons projecting to the heart's sinoatrial node to release acetylcholine, thereby decreasing heart rate, and increasing HRV (7). Individuals with high resting HRV (i.e. high vagal tone) have been shown to have more rapid recovery in their cardiovascular, immune and endocrine responses to stress (8,9).

In contrast, low HRV (i.e. low vagal tone) is considered a marker of sensitivity to stress. Low HRV has been associated with impaired stress response, inflammation, deregulation of glucose metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (10,11). Furthermore, low HRV has been linked to impaired neural activity in the prefrontal and limbic regions of the brain, which are involved in emotional and cognitive functioning (11,12).

Accumulating evidence reveals the link between vagal tone and physical and emotional health and wellbeing. For example, low vagal tone has been associated with a range of chronic health conditions, including migraine headaches, inflammatory bowel disease, epilepsy, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease (6,13,14). Furthermore, it has also been associated with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), loneliness, negative feelings, and poor emotional regulation. In contrast, individuals with a higher vagal tone have more effective regulation of emotional responses, strong social connections, positive emotions, and better physical health (15,16).

Vagal nerve stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation can be employed to increase the tone of the vagus nerve. It was first identified in the late 19th century when it was noted that epileptic seizures could be suppressed by massage of the carotid artery in the cervical region of the neck due to stimulation of the vagus nerve (17).

Vagal nerve stimulation using implanted electrical devices in the chest has been used for more than 20 years to control seizures in epilepsy patients and has been approved for treating drug-resistant cases of clinical depression (18). It is also used in chronic heart failure (19). More recently, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation devices that do not require surgical implantation (transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS)), have been approved for treating epilepsy (20), pain (21), depression (22), and migraines (23,24).

Currently, because of its influence on the immune system, researchers are investigating the vagus nerve’s role in treating inflammatory disorders such as traumatic brain injury (25), sepsis and lung injury (26), diabetes (27) and autoimmune conditions including rheumatoid arthritis (28,29), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (30,31) and Crohn’s disease (32,33).

Natural ways to stimulate the vagus nerve

Apart from electrical and transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation, there are natural ways to stimulate the vagus nerve and improve and rebalance the function of the ANS, which can have significant physiological and psychological health benefits including:

- Greater emotional stability

- A sense of calm and wellbeing

- Improved digestion and motility

- Reduced inflammation

- Improved ability to deal with stress

- Reduced loneliness

- Deeper relationship connections

- Reduced pain sensitivity.

Mind-body interventions

Slow breathing exercises

Controlled, slow breathing or diaphragmatic breathing has been demonstrated to be an effective means of preserving autonomic function and has been associated with benefits for numerous conditions, including anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain, insomnia, hypertension, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (34,35).

Vagus nerve activity is modulated by respiration. It is supressed during inhalation and facilitated during exhalation and slow respiration cycles (36). The SNS facilitates a brief heart rate acceleration during the inhalation phase of a breathing cycle. During exhalation, the vagus nerve secretes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. This release causes the heart rate to slow via the PNS and promotes a state of relaxation (37).

Typically, the breathing techniques used in contemplative activities such as yoga, meditation and tai chi include longer exhalations compared to inhalations (diaphragmatic breathing). Diaphragm breathing at six breaths a minute has been found to optimise the balance between the two branches of the ANS (38), making the system better able to adapt to both physical and mental stress.

Several clinical trials have demonstrated the positive effects of slow breathing on vagal activity, with a respiratory rate of 6 breaths/minute, reducing HRV and blood pressure (39,40,41).

Singing or chanting

The vagus nerve is connected to the vocal cords and the muscles at the back of the throat. Singing, humming, chanting, and gargling can activate these muscles and stimulate the vagus nerve. Furthermore, singing requires a slower than normal respiration which may, in turn, affect heart rate (42).

Om chanting is a meditation technique and an important exhalation exercise used in yoga, mantras, and different faiths such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Effective Om chanting causes a vibrating sensation around the ears, which is transmitted through the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, stimulating the vagal nerve (43) and deactivating the limbic system (44).

By increasing parasympathetic activity and reducing SNS activity, Om chanting has been found in clinical trials to reduce hypertension (45), alleviate menopausal symptoms (46), improve pulmonary function in healthy individuals (47) and reduce anxiety (48), depression and stress (49).

Meditation

Meditation is a conscious mental process that induces a set of integrated physiologic changes involved in the relaxation response. Studies suggest that at least three types of meditation may stimulate the vagus nerve indirectly. In small studies, loving-kindness meditation, mindfulness meditation, and Om chanting increased HRV (44,50). Some researchers think that conscious, deep breathing that accompanies meditation and other contemplative practices might underlie this effect (50).

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a well-established technique for developing the ability to self-regulate attention and emotion. Specifically, mindfulness can be defined as the cognitive ability to pay attention to the present moment without judgment or attachment to a desired outcome (51). Benefits of mindfulness include reduced pain and stress, improved cognitive functioning, increased positive emotion, and emotional regulation (51).

Several recent studies have provided preliminary evidence for mindfulness practice and its association with the increased parasympathetic tone, including increased HRV response (52,53). Furthermore, long-term mindfulness retreats have been shown to increase HRV (54). The increases in HRV and dominance of the PNS during mindfulness may partly be caused by changes in respiration which are modulated by the vagus nerve, since awareness of breathing is central to mindfulness practice (55,56).

Yoga

Numerous studies have shown the effect of various yoga practices for depression and anxiety (57,58), inflammatory conditions (59) and stress (60,61).

Yoga is known to exert its health benefits through several mechanisms of action including increasing neurotransmitter synthesis and neurotrophic factors, anti-inflammatory effects, HPA axis modulating effects (62) and effects on the vagus nerve (63).

A review of 59 studies with 2,358 participants suggested that yoga can affect autonomic regulation with increased HRV and vagal dominance during yoga practices. Regular yoga practitioners were also found to have increased vagal tone at rest compared to non-yoga practitioners. However, most studies were of poor quality, with small sample sizes, and insufficient reporting of study design and statistical methods and further rigorous studies with detailed reporting of yoga practices are required to determine the effect of yoga on HRV and vagal tone (63).

Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response

Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) is an experience of calm and tingles, a tingling sensation like electricity radiating from the head and neck, which affects the ANS. ASMR experiences are caused by a stimulus or trigger which is usually an audio-visual stimulus and entails whispering, scratching, tapping and other noises (64). A recent study of university students found significant differences in heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure occurred after watching a 3-minute ASMR video (65). Further rigorous studies are required to assess the effect of ASMR on vagal tone.

Laughter

Several studies have shown an association between laughter, mood, and better health (66), with researchers attributing some of its benefits to effects on the vagus nerve. In a pilot study, yoga laughter therapy for 4 weeks improved mood and increased HRV in patients awaiting organ transplantation (67). Furthermore, laughter is also sometimes a side effect of chronic vagus nerve stimulation performed in children with refractory epilepsy (68).

Positive emotions and positive social connections

Social isolation has a negative impact on mental, physical, and emotional health and overall mortality (69). A meta-analysis including 148 studies (308,849 participants) showed a 50% increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships. Furthermore, the influence of social relationships on mortality risk is comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality, such as smoking (69).

Several studies demonstrate that positive social interactions affect HRV. For example, one study of 2066 male civil servants in the United Kingdom (the Whitehall cohort) found a correlation between lower HRV and low social integration (70).

A randomised controlled trial demonstrated that compared to a control group, participants who undertook 6 weeks of loving-kindness meditation were able to self-generate positive emotions and improve vagal tone, which was mediated by increased perception of social connections (71).

One mechanism by which social isolation may negatively impact health outcomes is via altered ANS function. For example, a lower HRV has been correlated with adverse health outcomes, including reduced cognitive function, depression, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality (72).

Exercise

Aerobic exercise

During moderate-to-vigorous physical exercise (e.g. cycling, running, swimming, rowing), SNS activity and adrenaline production increases, elevating heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate above basal levels and concurrently, vagal control drops. However, after exercise, vagal control (measured as HRV) rises again, as the PNS and SNS branches of the ANS interact to restore heart rate to its baseline value (73,74).

Research indicates that regular physical exercise of moderate intensity can increase vagal tone (i.e., during rest) and vagal control (i.e. in response to a stressor) (75). Compared to sedentary controls, athletes have increased cardiac vagal tone as assessed with HRV (76). In addition, clinical trials demonstrate that regular aerobic exercise can significantly change HRV parameters that indicate enhanced vagal tone in sedentary adults (77).

Resistance training

Several clinical studies provide evidence that resistance training improves HRV in COPD (78), coronary artery disease (79) and obesity (80).

Nutrition

Probiotics

The vagus nerve's role in the microbiota-gut-brain axis is now well established; thus, therapies targeting the microbiota may positively affect vagal activity (6).

Animal studies have looked at the potential effects of probiotics on the vagus nerve, but human clinical trials are still lacking. Two studies found positive effects of L. rhamnosus and B. longum that were mediated via the vagus nerve (i.e. no effect in vagotomised mice) (81,82) and one study found that L. casei Shirota enhanced gastric vagal afferent activity (83). L. rhamnosus (JB-1) reduced stress-induced corticosterone and anxiety- and depression-related behaviour and induced positive changes in GABA receptors that were mediated by the vagus nerve (81).

Omega- 3 fatty acids

A growing number of studies have shown an increase in HRV and lower heart rate with higher fish intake or omega-3 fatty acid supplements (84,85,86,87).

In a study of obese children and adolescents at risk of developing cardiovascular disease, supplementation with fish oil (containing at least 400 mg eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and 120 mg docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) daily) over at least 3 months reduced HRV compared to healthy controls (84).

In a population-based cross-sectional study, increased fish consumption was significantly correlated with several HRV indices indicative of higher parasympathetic activity (88).

Fasting

Intermittent fasting and reducing calories both increase HRV in animal studies (89). Several human clinical trials demonstrate caloric restriction and weight loss are associated with increased HRV, and improved SNS/PNS balance (90,91).

Other interventions

Cold exposure

Acclimation to cold (10°C) has been shown to lower sympathetic activation and cause a shift toward increased parasympathetic activity (92). Studies have shown that following exercise, submersion to mid-sternal level in cool (14–15°C) (93) or facial immersion in cold water (10–12°C) (94) led to greater reactivation of the parasympathetic system as assessed by HRV indices.

This effect can be achieved by drinking cold water, dipping the face in cold water, or taking cold showers.

Massage

Many massage techniques have been shown to increase HRV/vagal tone including traditional Thai shoulder, neck, and head massage (95), traditional Thai back massage (96), Chinese head massage (97), and foot massage (98).

Self-massage of trigger points in the upper neck has been shown to increase HRV in patients with myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome (99).

Moderate pressure massage in underweight babies may assist with weight gain via increased vagal activity, which, in turn, stimulates gastric motility (100).

Takeaway

- The vagus nerve connects the brain to many organs throughout the body, including the gut. It plays a crucial role in the stress response via the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

- Heart rate variability (HRV) measures vagal tone (or activity) and is considered a marker of sensitivity to stress.

- Low HRV has been associated with inflammation, impaired stress response, depression and other chronic health conditions.

- Electrical and transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation has been approved for the treatment of refractory epilepsy and depression.

- There are many simple ways to stimulate the vagus nerve to support the ANS and promote psychological and physical health and wellbeing. These include mind-body interventions, exercise, nutrition, social connection and cold exposure.