A recent study highlights the association between a higher intake of animal and processed foods, alcohol and sugar, with higher levels of intestinal inflammatory markers (1).

The study investigated the relationship between 173 dietary factors and the microbiome of 1,425 individuals in 4 different cohorts: irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (223 individuals), Crohn's disease (205), ulcerative colitis (126), and healthy controls (871). The mean age of participants was 40-47 years. Dietary intake was assessed through food-frequency questionnaires, and shotgun metagenomic sequencing ![]() was used to profile gut microbial composition and function. Overall, 38 associations were identified between dietary patterns and microbial clusters. A meta-analysis across cohorts found 61 individual foods and nutrients that were associated with 61 microbial species and 249 metabolic pathways.

was used to profile gut microbial composition and function. Overall, 38 associations were identified between dietary patterns and microbial clusters. A meta-analysis across cohorts found 61 individual foods and nutrients that were associated with 61 microbial species and 249 metabolic pathways.

Processed and animal-derived foods were consistently associated with more Firmicutes, Ruminococcus species of the Blautia genus and endotoxin-synthesis pathways while plant foods and fish were positively associated with short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing commensals and pathways of nutrient metabolism (1). These associations were seen across the board in healthy participants as well as those with IBS or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Knowledge of the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory capacities of single compounds is increasing through functional experiments. The gut microbiome directly affects the balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. Microbial competition for nutrients plays a key role in controlling this balance (2).

Another recent study (in mice and humans) showed that a diet high in sugar and fat causes damage to Paneth cells, immune cells in the gut that help keep inflammation in check. When Paneth cells aren't functioning properly, the gut immune system is excessively prone to inflammation, putting people at risk of IBD and undermining effective control of disease-causing microbes (3).

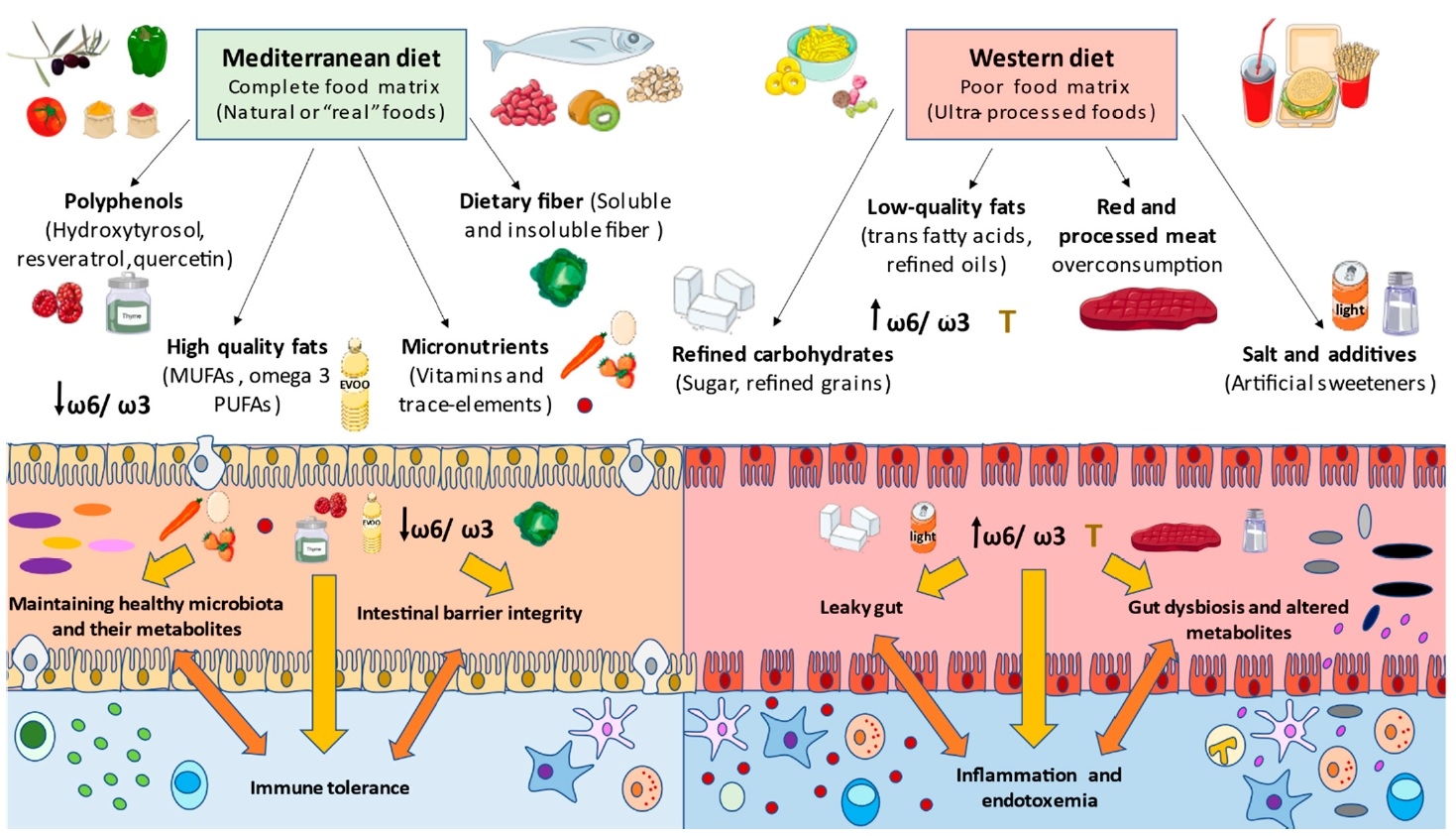

Diets that are high in red meat, animal fat, dairy products, salt, sugar and alcohol, and low in consumption of legumes, vegetables, fruits and seafood, are rich in refined and unhealthy products and are poor in micronutrients such as vitamin A or D, and fibre. This leads to critical changes in both gut microbiota and immune system, negatively affecting the gut integrity, thereby promoting local and systemic chronic inflammation (4,5,6). In contrast, some functional components found in healthy diets, such as probiotics, prebiotics and polyphenols, are beneficial for the restoration of gut health (7).

A previous study showed that participants who consumed a greater amount of animal protein presented a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, whereas those who consumed less animal protein, had a higher concentration of Bacteroidetes. Participants that consumed more polysaccharides and plant proteins showed higher concentrations of SCFA (8).

The deleterious effects of the consumption of added sugars, particularly from sugar-sweetened drinks, have been reported in the gut microbiota, promoting an increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and reducing the proportion of favourable butyrate-producers such as Lachnobacterium (9). Likewise, added sugars promote increased gut permeability and endotoxaemia ![]() , leading to inflammation and systemic complications (10).

, leading to inflammation and systemic complications (10).

The gut microbiota directly influence the intestinal immune system but also affect systemic immune components and are implicated in a growing number of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, ranging from diabetes to arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (11). Gut dysbiosis and associated inflammation have also been implicated in cancer and cardiometabolic disorders (12,13).

Figure 1. Effect on the gut microbiome of a typical western diet (processed foods, sugar, red meat) compared to the Mediterranean diet (14) CC BY 4.0

Conclusion

This study provides additional support for the idea that diet can be a rational strategy for the prevention and management of chronic inflammatory disorders of modern society. Western diet and food industrialisation parallel the rising incidence of IBD in previously considered low-risk countries, and functional studies already show that additives included during food processing, such as artificial sweeteners, are associated with pro-inflammatory changes in the gut microbiome (15,16,17,18).

While this study highlights the association between processed foods and intestinal inflammation, it’s important to note that other factors such as genetics, ethnicity and environmental influences might also impact inflammation. These factors were not taken into account in the present study. Nonetheless, the results provide additional insight into the importance of a diet that is minimally processed.

Long-term dietary interventions may be most suited for the modulation of the gut microbiota. Although extreme short-term dietary changes may still change the gut microbiota (19,20), there is a tendency for microbial resilience in adults that correlates with long-term habitual diet (21,22,23).

Modulation of gut microbiota through diets enriched in vegetables, legumes, grains, nuts and fish and a higher intake of plant over animal foods, has the potential to prevent intestinal inflammatory processes at the core of many chronic diseases.